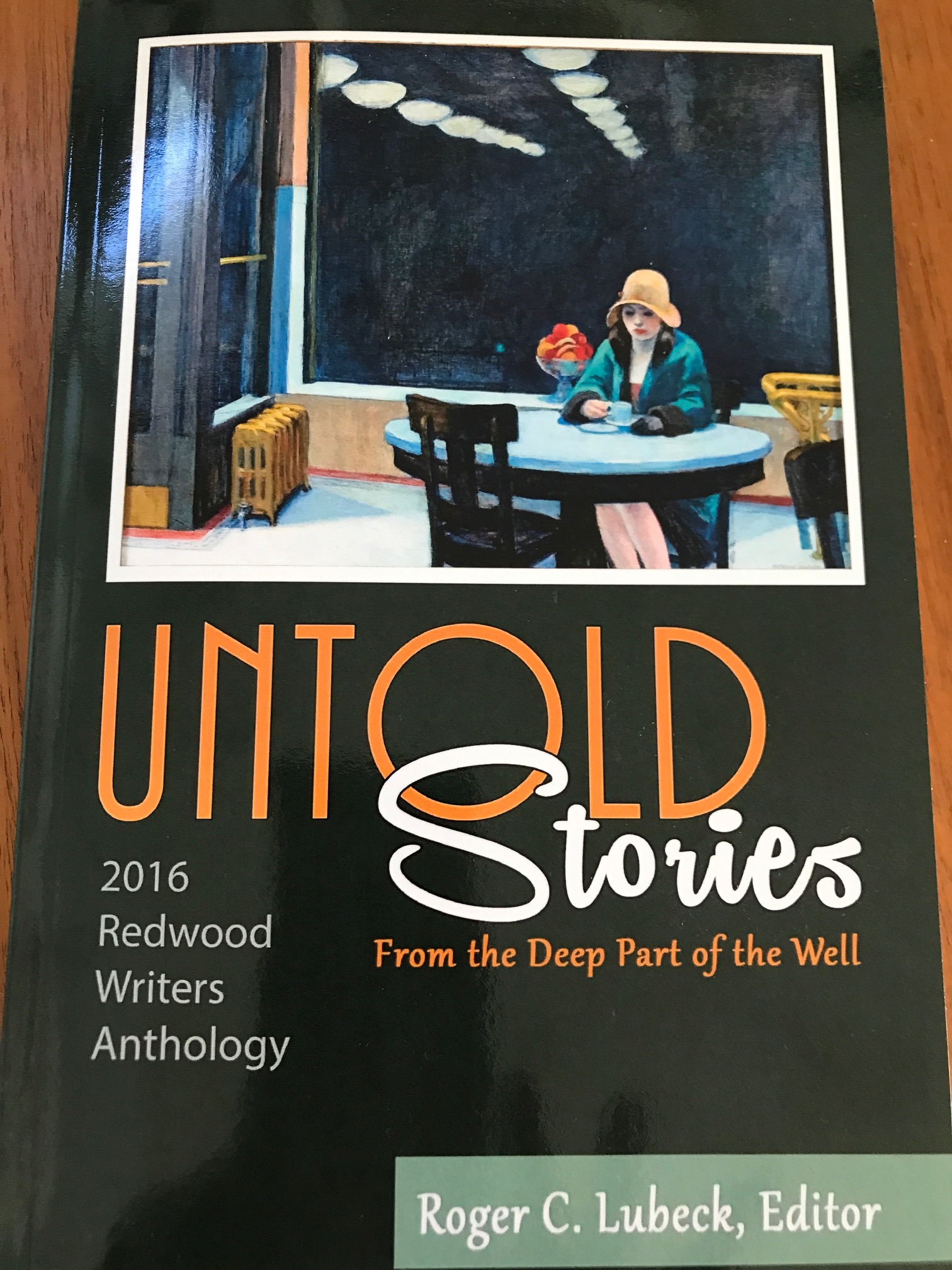

Excerpt of this short story from 2016 Redwood Writers Anthology, Roger C. Lubeck, Editor

The Drop-off

Marilyn Skinner Lanier

Her two young children skip alongside her this chilly March morning in Seoul. They pelt her with questions as they marvel at the brass pots hanging above their heads and the food stalls heaped with dried fish, raw mussels, ginger root, apples, and bins of rice.

“Oma! Oma!” they exclaim. “Is that fish soup? Can we have some?” The enticing smells draw them to the stainless steel cauldron. But Jeong Yeob charges ahead through the morning throng, tightly clasping their hands and ignoring their chatter. The trio skirts bicyclists, taxis belching diesel fumes, and crowds heading cross directions through the alleys and narrow streets of the busy Myeongdong district.

The congestion and clamor of the street remind her of how much she dreaded this trek with her children through downtown Seoul when she found the address of the adoption center in the phone book a few weeks ago. At the same time, she was relieved that the Yosu branch of the international adoption agency was within walking distance of her house. She could get the children there without taking a taxi and, more important, without drawing her husband’s attention.

She had practiced what she would say to him if he asked where they were going.

“To the market,” she told him. “We need eggs. The baby’s asleep,” she said, nudging the children toward the front door.

Her heart was beating hard and fast as she helped the children with their coats. They must have detected her nervousness because neither said a word. Her husband didn’t respond either. In fact, he didn’t look up when they slipped out.

Their march to the adoption center was a solution to the problem that had consumed her ever since her third child, a boy, was born eighteen months ago. He was the first child of her marriage to Lee Kyung. She had moved to Seoul to find work after the father of Chul Moon and Yoora had died at sea. Actually, she still wasn’t certain whether he was dead or not. But he never returned to her parents’ farm south of Seoul after leaving for a month-long commercial fishing voyage, so she figured he must have died or taken up with another woman. Either way, she knew she had to find employment, and Seoul was the center of commerce and jobs in South Korea. A year later, she moved there with her two children. Chul Moon was four years old, and his younger sister, Yoora, was two-and-a-half.

She met Lee Kyung at the shoe factory on the outskirts of Seoul, not far from the East Gate, where she got her first job. He was her line supervisor. Although he was a taskmaster, she was attracted to his rugged good looks, and she readily agreed to his proposal after dating him for only a few months, certain that marriage would give her and her children a better life.

After her second son was born, she registered herself and the new baby as part of the Korean family registration process, a tradition called Hojuk. She learned, however, that neither Chul Moon nor Yoora could be registered under their stepfather’s name, and the same was true for their father since she had never married him. Her heart sank. Chul Moon and Yoora would be forever considered bastard children, without social recognition in their native land.

As they walk past slabs of fresh meat strewn over blocks of ice covered by gunny sacks, she is reminded of the night she and Chul Moon had endured the frigid night air as they waited for her husband to unlock the front door when they returned from the neighborhood meat market. She sought help at the nearby police station, where a policeman agreed to accompany them home. After a lot of shouting and pounding on their front door by the officer, it suddenly flew open, her husband bracing himself and snarling at them in a drunken stupor.

“He’s a mean man!” Chul Moon declared later, after her husband had dozed off on the futon that was shoved against the living room wall for the night. She squeezed her son’s small hand and looked away. Her husband had locked them out of the house before. Another time, Chul Moon was upset over the belting he had received for refusing to eat moldy kimchi. “It’s rotten!” he had insisted, pointing his shaking finger at the offending food. But her husband was furious at the young boy’s challenge to his order. There were other incidents like this, always focused on Chul Moon.

More than once she had encountered Chul Moon and his young sister arguing about her husband, usually after Chul Moon had been struck by him or received a belting for misbehaving. Chul Moon would call him a “mean man” while Yoori would insist he was a “nice man.” So far, Yoori had been spared his abuse. Kyung had taken a liking to her little girl. Must be her chubby cheeks or that she always obeyed him…

“The Drop-off” continued in the anthology, pages 273-278